The Science of Nutritional Ketosis and Appetite

Now We Know Why You Can Lose Weight with Reduced Hunger and Cravings

The challenge of losing weight and then keeping it off can be daunting, especially if you have ridden the diet roller-coaster in the past. Dieting, exercise and repeated feats of sheer willpower are typically met with temporary weight loss followed by weight regain and mounting frustration. If you feel like whenever you count and/or restrict calories your appetite begins a progressive climb the longer you purposefully count or restrict your calorie intake, you may be on to something. Our bodies have an innate survival mode that kicks in to maintain energy balance when our stored energy reserves (i.e., body fat) are threatened. Obesity and metabolic diseases, like type 2 diabetes, can perturb these natural signals the body uses to regulate appetite and energy balance, making weight loss even more difficult. Here we explore the scientific basis behind appetite, the various factors that regulate how we experience hunger and the subsequent effect those signals have to counteract weight loss. We also look at the ways in which a well-formulated ketogenic diet (WFKD) affects appetite and the multiple mechanisms through which this manner of eating can help you lose weight and maintain the weight loss while simultaneously improving your health.

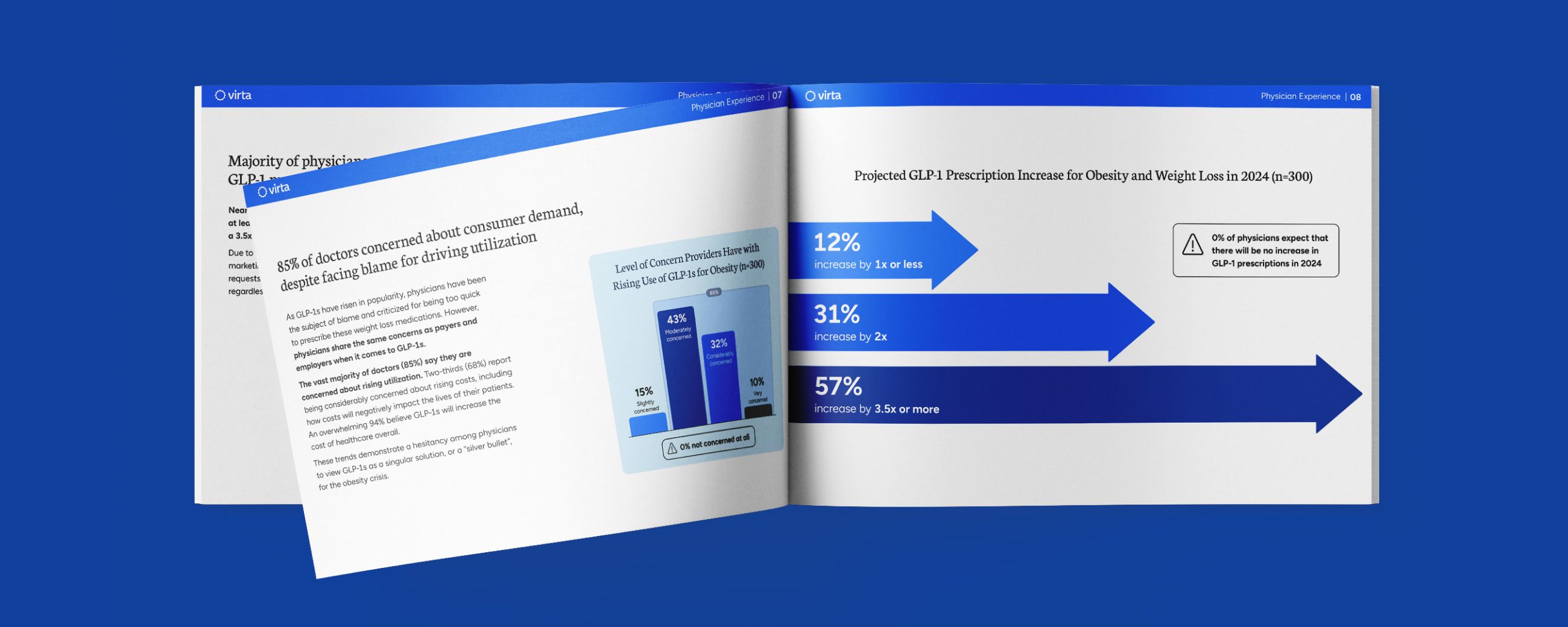

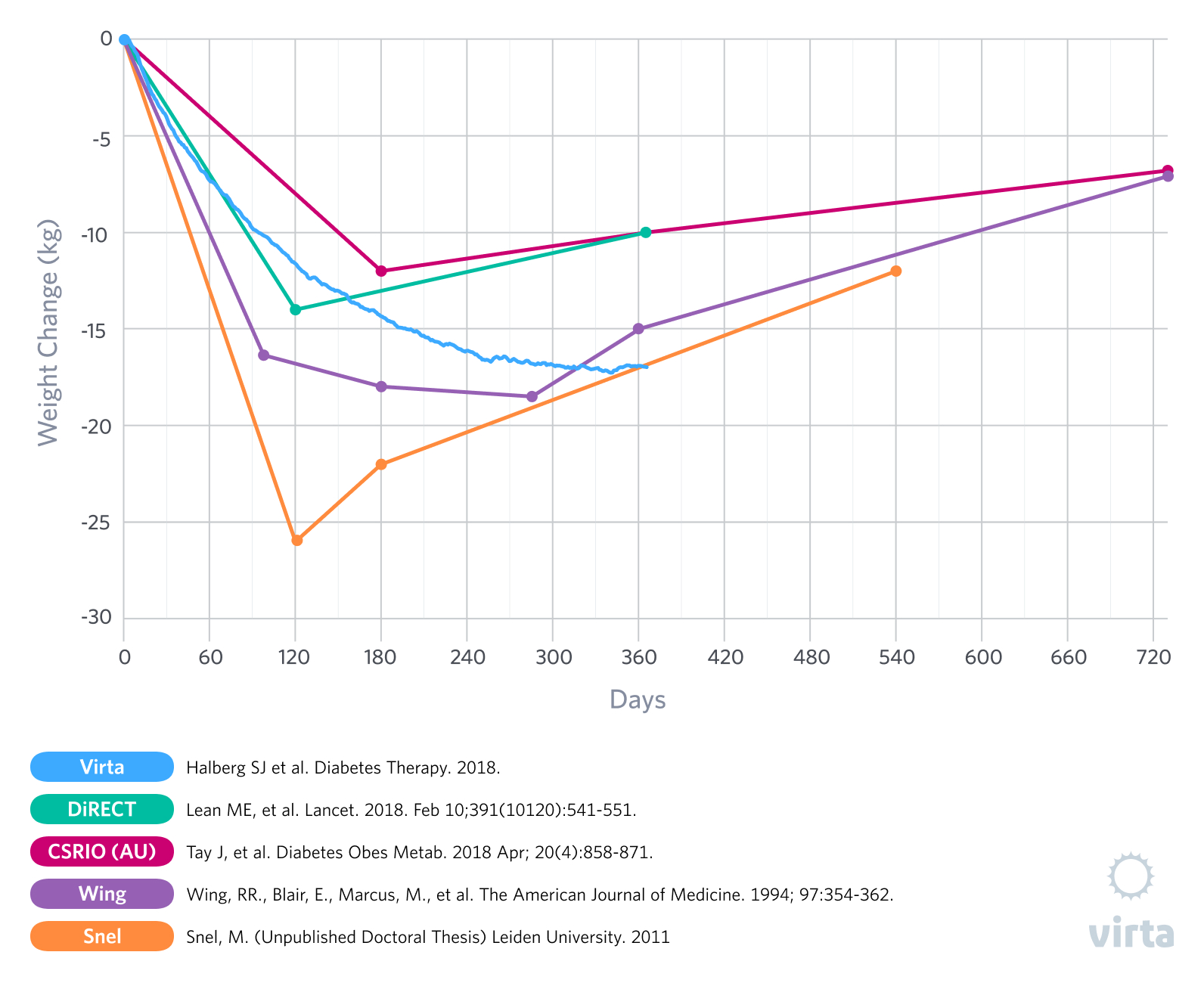

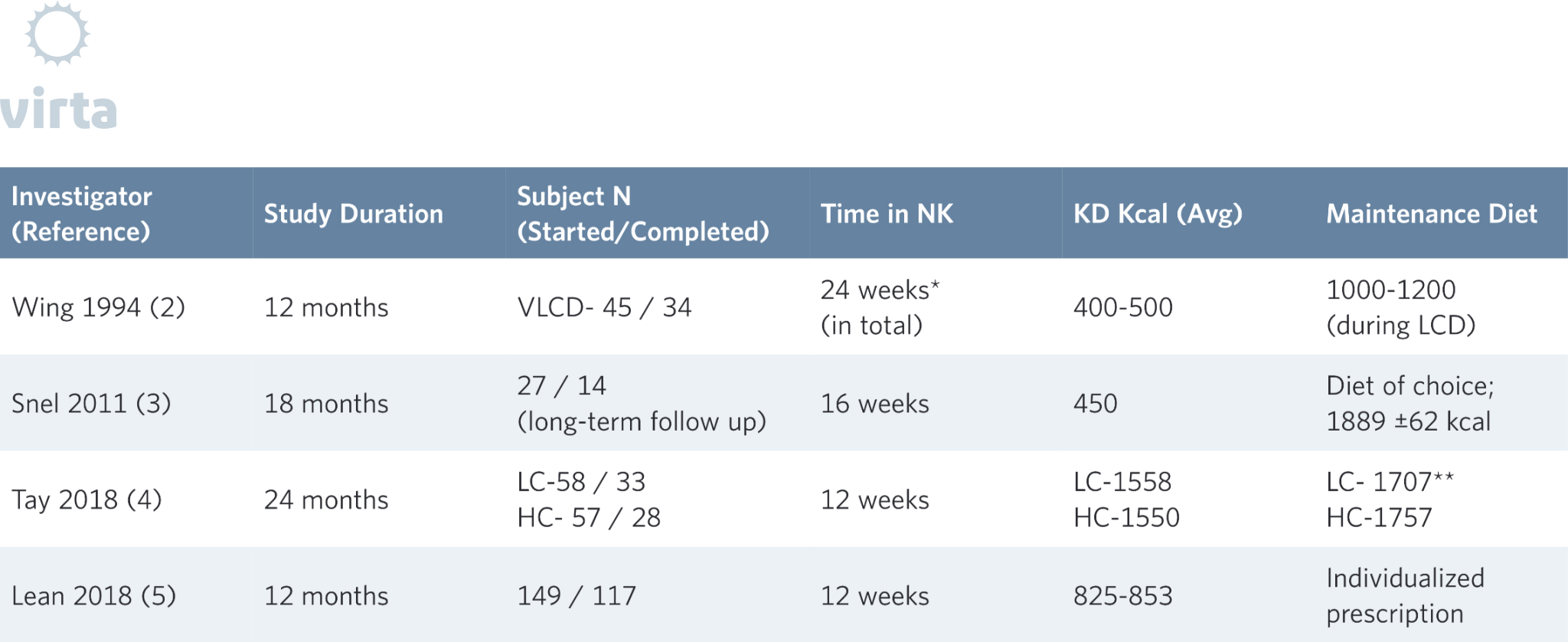

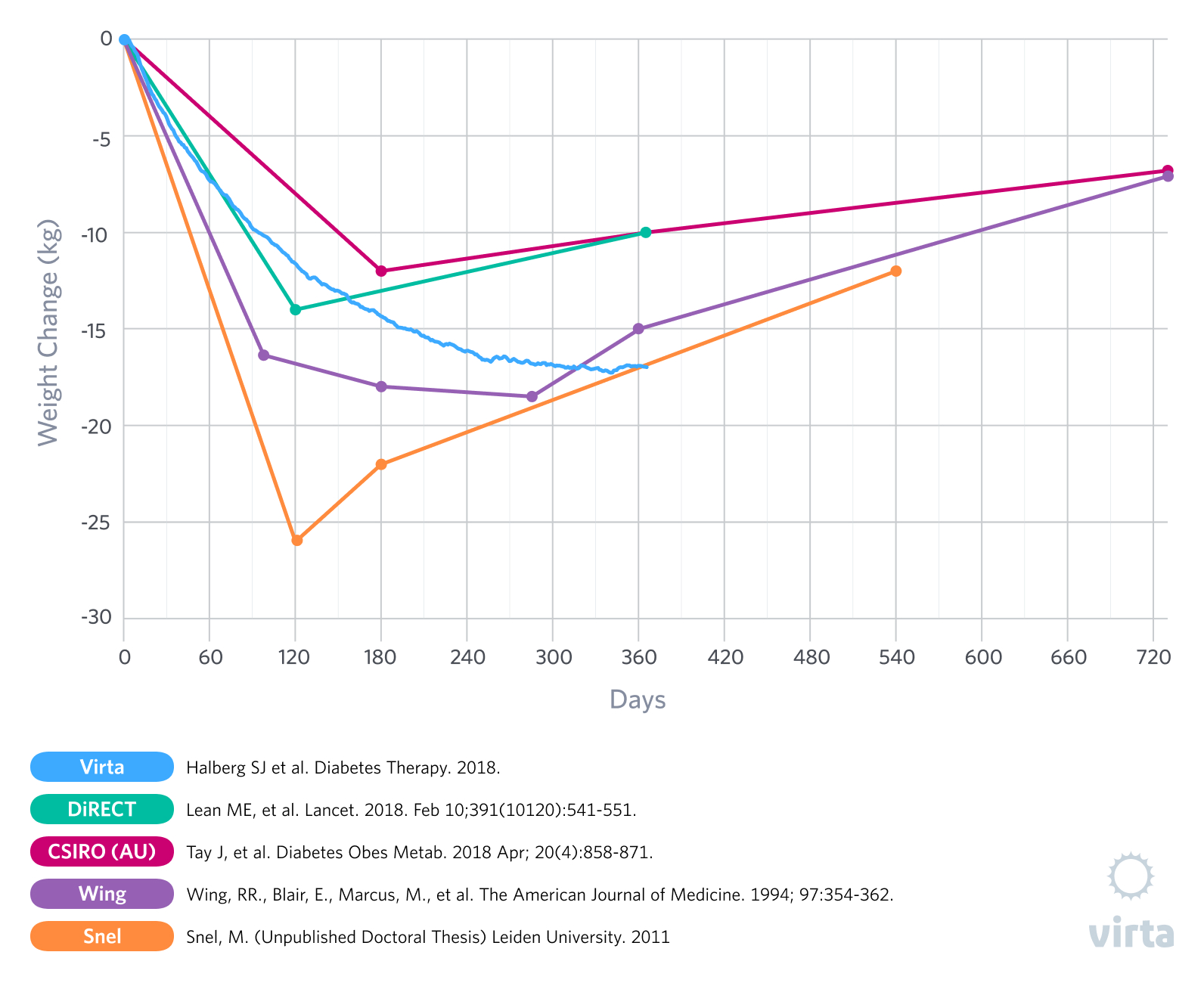

For the past few decades, studies looking at obese humans that were randomized to compare very low carbohydrate diets and higher carbohydrate diets have consistently demonstrated greater initial weight and body fat losses with the low carbohydrate diets designed to induce nutritional ketosis (1). But in almost all such studies that lasted a year or longer, within 6 months the initial weight losses stopped and weight regain had begun, thus reducing some of the advantages of a carbohydrate restricted diet. This observation of a what appears to be a transient advantage of a ketogenic diet has been most prevalent in studies of patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) that were prescribed a prepared formula meal or whole food ketogenic diet for 3-5 months, followed by transition back to an increased carbohydrate intake (2,3,4,5).

*12 weeks VLCD, 12 weeks on LCD, then 12 weeks back VLCD

**21-24 months daily kcal

VLCD = very low-calorie diet

We have observed that most individuals who are instructed to eat a well-formulated ketogenic diet to satiety can lose substantial amounts of weight while experiencing reduced hunger and cravings. In other words, something about nutritional ketosis promotes weight loss by a combination of reduced appetite and/or better access to body fat stores for fuel. This effect of nutritional ketosis has been attributed by others to a variety of causes ranging from increased energy expenditure (aka ‘metabolic advantage’) to aversion or boredom caused by the restricted food options on a high fat diet. But perhaps there are more nuanced factors at work here.Figure 1.

Weight Loss on a Ketogenic Diet

In our recently published results from the Virta/IUH Diabetes Reversal Study (6), we reported an average 12-month weight loss of greater than 12% in patients with T2D, where weight loss continued out to 8 months and was then sustained out to 12 months without even a trend for weight regain (Figure 1). Additionally, at week 10 in this study, the patients reported less hunger than at baseline (7). But of particular interest is how this result was achieved -- from day 1 through day 365 these patients were instructed to eat a well-formulated ketogenic diet to satiety. As a result, supported by the Virta remote continuous care treatment, our patients maintained average blood ketones of 0.6 mM after 10 weeks and 0.4 mM after 12 months. What this means is that these remarkable and lasting weight loss results were achieved without purposeful calorie restriction or the need to resist persistent hunger and were associated with long-term adherence to a ketogenic diet.

By definition, most weight loss diets restrict total calories and counsel patients to explore behavioral methods to deal with hunger and cravings. For example, we are told that when we are hungry, drink a big glass of water, go for a walk, or eat a high fiber low energy snack. But this ignores the fact that appetite, hunger, and cravings are symptoms of the body’s innate drive to restore energy balance. Severely restricting calories or markedly increasing the body’s energy expenditure with high volume exercise predictably brings on this compensatory response (8). Therefore, the longer an individual maintains the caloric restriction and the greater the amount of weight loss, the more compelling the appetite signals (9).

Hormones and Hunger

Twenty-five years ago, the only known appetite-controlling hormone was insulin. When blood insulin levels are high, glucose gets stored as glycogen and fats get stored in adipose tissue. The resulting reduction in circulating fuels, such as glucose and free fatty acids, then stimulates appetite. This leads to the common experience of being hungry 2-3 hours after a high carbohydrate, low fat meal. In fact, many people are still arguing that increased insulin is the dominant signal that makes us become obese. But in the interim, we have discovered many other circulating and cellular signals that communicate the body’s energy status and regulate energy intake (aka appetite) as well as metabolism. Among these regulatory hormones are leptin (made primarily in adipose tissue), and ghrelin (made in the upper digestive tract). Both have specific receptors in the brain that transmit their biochemical message into behaviors – for leptin it is “eat less” and for ghrelin it is “eat more”.

It turns out that how these signaling hormones interact with insulin is complex. Add the increased underlying inflammation that is characteristic of obesity and diabetes, and the picture gets even more complex in ways that continue to promote obesity. Fortunately, we now know that when you add a well-formulated, sustained ketogenic diet to this picture it changes dramatically for the better, but in a pattern that is hard to explain. Yes, blood insulin levels go down, but the satiety hormone leptin also goes down. In fact, individuals on a low carbohydrate diet who experience weight loss exhibit a significantly greater reduction in leptin levels compared to those on a low-fat diet (10). That would normally be a signal to eat more, but here’s a key fact -- the brain’s sensitivity to the leptin signal goes way up when on a well-formulated ketogenic diet.

Another key fact – the brain’s response to leptin is inhibited by inflammation (11), resulting in leptin resistance. Since we now know that inflammation is dramatically reduced by sustained nutritional ketosis (12, 13), it appears that the reduction in leptin resistance due to reduced inflammation more than compensates for the lower leptin levels. In other words, on a well-formulated ketogenic diet the brain perceives a greater satiety response to less leptin. This reduction in inflammation and increase in sensitivity to leptin, together with the reduced blood insulin levels characteristic of nutritional ketosis can explain the paradox as to why we see a decrease in appetite with nutritional ketosis.

If this seems like a challenge to comprehend, it is. But put as simply as possible, nutritional ketosis reduces elevated insulin levels and inflammation, which allows the normal signals from excess body fat stores to tell the brain “Eat less!” Therefore, when heavy people eat a well-formulated ketogenic diet to satiety, they tend to lose quite a bit of weight until the balance of these signals naturally guides them to a stable lower weight.

For many of our readers, this is probably more than enough science. For the rest of you, what follows are the details and additional references that back up this very complex but important story.

The Science of Appetite: What We Can Learn From Very Low Calorie Diets

As anyone who has attempted to lose weight can attest, appetite often becomes a significant factor in the weight loss process. A well-documented example of the relationship between weight loss and appetite can be observed in studies that utilize medically monitored very low-calorie diets (VLCD) with obese subjects. These diets, often in the range of 400 to 800 kcal a day, typically lead to ketosis soon after onset. The ketosis that results from this extreme caloric restriction likely contributes to the reduction in reported hunger (14). As you would expect, in the weeks or months that patients follow these diets they typically experience significant losses of body weight, often ranging from 10-20% (2,3,15,16). Naturally however, this level of caloric restriction is not sustainable for the long-term and individuals must return to a maintenance level of food intake. This is where the challenges begin.

When transitioning from a VLCD after weight loss there is often a shift in appetite regulating hormones in the direction of an increased drive to eat (15)(16). And, while ketosis reduces the perception of hunger, going back to regular food and /or adding more carbohydrate and reversing ketosis tends to have the opposite effect, resulting in increases in ghrelin and hunger above pre-weight loss levels (15). What does this mean practically? For many (if not most) individuals, it means that if they go back to eating the way they did before weight loss, there is a good chance they will regain the weight they have lost and possibly more.

To further exacerbate the challenges of maintaining weight loss after a few months on a VLCD, patients are often transitioned to a diet either moderate (30-50%) or high (>50%) in carbohydrate that resembles the one that contributed to their metabolic dysfunction in the first place. As we have mentioned before, insulin resistance can be viewed as functional carbohydrate intolerance (17). Individuals with metabolic diseases, such as pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes, frequently do not fully resolve their underlying insulin resistance despite appreciable weight loss and thus do not do well when transitioned back to a carbohydrate-rich diet. Seen from this perspective, they would be expected to benefit from a continued restriction of carbohydrate intake to maintain weight loss. The glycemic improvements seen with a VLCD can also rebound to pre-diet levels when the patient is reintroduced to a large amount of carbohydrate. Would these patients have fared better had they been transitioned from the VLCD onto a sustainable ketogenic diet that allowed them to sustain nutritional ketosis for metabolic health? Perhaps. That is definitely a study we would like to see, as our IUH diabetes reversal study showed progressive weight loss out to 8 months and then weight stability to month 12 (6).

Mechanisms of Appetite Regulation and Leptin Resistance

Many researchers believe that the reduction in perceived hunger as well as the changes in some of the appetite regulating hormones seen with ketogenic diets and VLCD interventions are attributable to ketosis. Mechanistically, this may be due to an effect of ketosis on the activity of appetite-regulating hormones themselves, or ketones acting on the brain directly, or a relationship with the gut microbiota. More likely, it is a combination of all of these (18). Studies looking at patients prescribed a VLCD and hunger have shown that subjects who maintained beta-hydroxybutyrate levels of 0.3mM or greater had suppressed ghrelin levels, while those who were not in ketosis had ghrelin levels above baseline (15). Thus, harnessing the power of nutritional ketosis in a weight loss effort may not only contribute to initial weight loss but may also play an important role in sustainability and weight maintenance.

We mentioned appetite-regulating hormones and the influence they have on feeding behavior, especially with dieting and weight loss. These are important because they appear to have a substantial role in how our body tries to regulate how much we eat. Two of the most commonly studied hormones with respect to neuroendocrine appetite factors are ghrelin and leptin. Ghrelin, often referred to as the “hunger hormone”, is a multifaceted orexigenic hormone produced by the gut that, among other actions, influences acute meal initiation (19). Leptin is satiety hormone that is secreted mainly by adipocytes and regulates energy intake as well as expenditure (20), in large part due to the leptin-responsive signaling cascades in the hypothalamus (21). Together they both have an impact on our appetite and how we respond to changes in food intake and body fat content.

What is interesting about leptin is that its influence extends beyond appetite regulation and it may have a complex role in the pathophysiology of obesity (22) as well as immune function (23). Similar to what we see with insulin resistance, there is evidence of leptin resistance in individuals who are obese. This indicates that while obesity often coincides with increased circulating leptin levels, there is a resistance to its anorexigenic signals to reduce food intake. So even though an elevated blood leptin level is supposed to reduce hunger, the body becomes resistant to the signal and doesn’t get that message. As a result, leptin resistance can contribute to obesity and hyperphagia rather than act to suppress it (24).

This paradox of increased appetite and obesity occurring despite elevated blood leptin levels may be partially attributable to inflammation (11). You may have heard obesity referred to as a chronic low-grade inflammatory state, but in this instance, leptin resistance may be due to enhanced immune and inflammatory responses in the brain. The neuroregulatory aspects of appetite have made it clear that the brain and central nervous system (CNS) are involved in energy homeostasis and food-seeking behaviors. Thus, as the master regulator of appetite, the hypothalamus integrates peripheral and central pathways to mediate appetite signals.

In fact, an up-regulation of pro-inflammatory pathways in the hypothalamus, triggered by a pro-inflammatory diet rich in a combination of sugar and saturated fat, has been shown to effect chronic energy imbalance and changes in fat mass (11). Because leptin acts within the hypothalamus, the over-activation of immune cells associated with the hypothalamus can impair leptin signaling (25). For example, C-reactive protein has been shown to actively inhibit leptin’s satiety signal (26). This multi-dimensional inflammatory response likely begins before overt obesity and contributes to the overall development of metabolic dysfunction (27).

Another proposed mechanism to explain leptin resistance in the brain is hypertriglyceridemia. In this scenario, elevated blood triglycerides cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and impair both the transport of leptin across the BBB as well as inhibit receptor function in the brain, thereby promoting leptin resistance (28)(29). Because it has been repeatedly demonstrated that carbohydrate restriction reduces triglyceride levels, this is an additional explanation for the significantly lower leptin levels observed with ketogenic diets (10), adding to the anti-inflammatory effects of the diet which increase leptin sensitivity and sustain the anorectic signaling effects.

Aberrant leptin signaling is one way in which increased inflammation is relevant to appetite and influences hunger and food seeking behaviors. When we don’t have the leptin signal telling us to stop eating we have a greater tendency to over-consume food and gain weight. If functioning optimally, leptin also indirectly effects the hedonic responses to feeding; which helps us avoid over-eating simply because something tastes good instead of eating for true hunger (30). Leptin, therefore, may end up being more of a factor in the maintenance of weight loss than in losing weight itself (31). This relatively new information about hypothalamic inflammation as a contributor to diet-induced obesity could advance our understanding of how diet and inflammation exacerbate symptoms of metabolic syndrome and T2D (32).

Nutritional Ketosis and Appetite

At this point you may think this sounds like we are fighting an unwinnable war against biology. Thankfully however, what we continue to learn about a ketogenic diet shows that it is a formidable ally in our efforts to control appetite as well as inflammation. The dramatic reductions in inflammatory biomarkers seen with a WFKD, including significant reductions in total white blood cell count and CRP, may positively impact the hypothalamic inflammation that contributes to diet-induced leptin resistance and resultant weight gain (12)(13). In other words, the anti-inflammatory properties of nutritional ketosis can be directly linked to improved satiety (14) giving us a one-two punch for successful weight loss and maintenance.

In addition to the potent anti-inflammatory effects of nutritional ketosis, recently the use of exogenous ketones has also been shown to decrease the postprandial rise of ghrelin and the perception of hunger (33). Thus, it appears that both nutritional ketosis and perhaps the increase in beta-hydroxybutyrate resulting from the consumption of exogenous ketone esters can modulate appetite signaling hormones and contribute to a reduction in hunger. While this research on exogenous ketones is very early stage, it highlights the multiple and varied roles ketones can play in the energy balance equation.

What this new perspective on appetite signaling shows us is that consistently following a well-formulated ketogenic diet promotes improvements in metabolic health that go beyond weight loss and contribute to long-term well-being. So, whether you are just starting to explore the idea of using nutritional ketosis to improve your health or you are considering whether or not this is something you can do long-term, it is becoming more evident that nutritional ketosis can enhance appetite control signals, reduce inflammation and facilitate diet adherence and sustainability. These advantages can go a long way towards supporting your health while not requiring you to suffer through constant hunger and the frustration of roller-coaster weight fluctuations.

The information we provide at virtahealth.com and blog.virtahealth.com is not medical advice, nor is it intended to replace a consultation with a medical professional. Please inform your physician of any changes you make to your diet or lifestyle and discuss these changes with them. If you have questions or concerns about any medical conditions you may have, please contact your physician.

This blog is intended for informational purposes only and is not meant to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or any advice relating to your health. View full disclaimer

Are you living with type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, or unwanted weight?

- Sackner-Bernstein J, Kanter D, Kaul S. Dietary Intervention for Overweight and Obese Adults: Comparison of Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diets. A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 20: 10(10)

- Wing, RR., Blair, E., Marcus, M., et al. Year-Long Weight Loss Treatment for Obese Patients with Type II Diabetes: Does Including an Intermittent Very-Low-Calorie Diet Improve Outcome? The American Journal of Medicine. 1994; 97:354-362.

- Snel, M. The Effects of a Very Low Calorie Diet and Exercise in Obese Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis) Leiden University. 2011

- Tay, J., Thompson, CH., Luscombe-Marsh, ND., et al. Effects of an energy-restricted low-carbohydrate, high unsaturated fat/low saturated fat diet versus a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in type 2 diabetes: A 2-year randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018; 20(4):858-871.

- Lean, MEJ, Leslie, WS., Barnes, AC. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2018; 391: 541–51

- Hallberg, SJ., McKenzie, AL., Williams, PT., et al. Effectiveness and Safety of a Novel Care Model for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes at 1 Year: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized, Controlled Study. Diabetes Ther. 2018; 9:583–612.

- McKenzie, AL., Hallberg, SJ., Creighton, BC., et al. A Novel Intervention Including Individualized Nutritional Recommendations Reduces Hemoglobin A1c Level, Medication Use, and Weight in Type 2 Diabetes. JMIR Diabetes. 2017;2(1):e5

- Malhotra, A., Noakes, T., Phinney, S. It is time to bust the myth of physical inactivity and obesity: you cannot outrun a bad diet. Br J Sports Med. 2015; 49(15)

- Doucet E., Imbeault P., St-Pierre S., et al. Appetite after weight loss by energy restriction and a low-fat diet-exercise follow-up. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(7):906-914.

- Volek, JS., Phinney, SD., Forsythe, CE., et al. Carbohydrate Restriction has a More Favorable Impact on the Metabolic Syndrome than a Low Fat Diet. Lipids. 2009; 44:297-309.

- de Git, KCG., Adan, RAH. Leptin resistance in diet-induced obesity: the role of hypothalamic inflammation. Obesity Reviews. 2015; 16: 207–224

- Forsythe, CE., Phinney, SD., Fernandez, ML., et al. Lipids. 2008; 43:65–77 Comparison of Low Fat and Low Carbohydrate Diets on Circulating Fatty Acid Composition and Markers of Inflammation. Lipids. 2008; 43:65–77.

- Bhanpuri , NH., Hallberg, SJ., Williams, PT., et al Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: an open label, non-randomized, controlled study. Cardiovasc Diabetol (2018) 17:56.

- Gibson, AA., Seimon, RV., Lee, CMY., et al. Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2015; 6: 64–76

- Sumithran, P., Prendergast, LA., Delbridge, E., et al. Ketosis and appetite-mediating nutrients and hormones after weight loss. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013; 67: 759-764

- Nymo, S., Coutinho, SR., Jorgensen, J., et al. Timeline of changes in appetite during weight loss with a ketogenic diet. International Journal of Obesity. 2017; 41: 1224–1231

- Volek, JS., Phinney, SD., The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living. Beyond Obesity, LLC, 2011.

- Paoli, A., Bosco, G., Camporesi, EM., et al. Ketosis, ketogenic diet and food intake control: a complex relationship. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015; 6: Article 27

- Pradhan, G., Samson, SL., Sun, Y. Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013; 16(6): 619–624.

- Klok, MD., Jakobsdottir, S., Drent, ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obesity Reviews. 2007;8:21-3

- de Luca, C., Kowalski, TJ., Zhang, Y., et al. Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuronspecific LEPR-B transgenes. J. Clin. Invest. 2005; 115:3484–3493.

- Farooqi, IS., O’Rahilly, S., Leptin: a pivotal regulator of human energy homeostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009; 89(suppl):980S–4S

- Perez-Perez, A., Vilarino-Garcia, T., Fernandez-Riejos,P., et al. Role of leptin as a link between metabolism and the immune system. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2017; 35: 71–84

- Morris, D.L., Rui, L.Recent advances in understanding leptin signaling and leptin resistance. American Journal of Physiology Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009; 297: E1247–E1259.

- Cai, D. Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in overnutrition-induced diseases. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;24(1):40-47

- Hribal, ML., Fiorentino, TV., Sesti, G., Role of C Reactive Protein (CRP) in Leptin Resistance. Curr Pharm Des. 2014; 20(4):609-615

- Cai, D. Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in overnutrition-induced diseases. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;24(1):40-47

- Valdearcos,M., Xu, AW., Koliwad, SK. Hypothalamic Inflammation in the Control of Metabolic Function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2015. 77:131–60

- Banks, WA., Coon, AB., Robinson, SA., et al. Triglycerides Induce Leptin Resistance at the Blood-Brain Barrier. Diabetes. 2004; 53: 1253-1260.

- Banks, WA., Farr, SA., Salameh, TS., et al. Triglycerides cross the blood-brain barrier and induce central leptin and insulin receptor resistance. International Journal of Obesity. 2018; 42: 391-397.

- Farr, OM., Fiorenza, C., Papageorgiou, P. et al. Leptin Therapy Alters Appetite and Neural Responses to Food Stimuli in Brain Areas of Leptin-Sensitive Subjects Without Altering Brain Structure. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014; 99 (12):E2529–E2538

- Kissileff, HR., Thorton, JC., Torres, MI., et al. Leptin reverses declines in satiation in weight-reduced obese humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012; 95:309–17

- Stubbs, BJ., Cox, PJ., Evans, RD. A Ketone Ester Drink Lowers Human Ghrelin and Appetite. Obesity. 2018; 26:269-273.